In Capital Block, a resettlement area in Gwanda, Matabeleland South, villagers are growing frustrated. Many once welcomed Chinese mining investments with the hope of development and improved livelihoods but those hopes have turned into anger.

“When they came, we saw development in our area,” says Phineas Siziba, a villager. “We expected things like clean, sustainable water sources near our homes. But now, we’re worse off.”

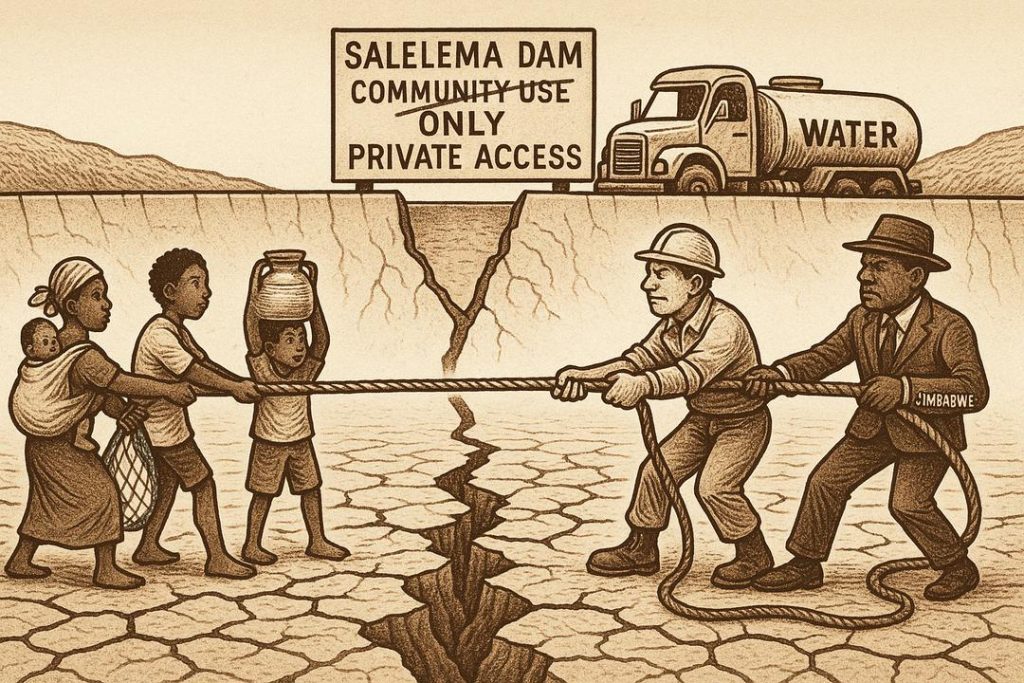

Communities in Vova, Plot 18, and around Salelema Dam rely on limited water sources, including the dam itself—which often runs dry—and another dam at Plot 17, which is far from most homesteads.

Instead of easing the water crisis, residents say Chinese mining companies extract water directly from these local sources, sometimes operating within the dams.

“They have machinery and ways of instilling fear. We are forced to compete with them for water, and we always lose.”

Phineas Siziba, a villager

Villagers say the miners fish in the dams using electric shockers—an illegal practice under local rules—and leave behind degraded land and polluted water.

Philani Moyo*, a village head from Magedleni in Gwanda North, calls the operations “daylight robbery.”

“These people don’t care about giving back. They are like maggots—only here to consume,” he says.

The Chinese mining boom in Matabeleland South was expected to reduce unemployment and stimulate local economies. Instead, residents report worsening poverty, deforestation, and unchecked extraction of minerals, sand, and water.

According to the Centre for Natural Resource Governance (CNRG), communities with natural resources are experiencing increased repression and deepening poverty.

“Those hosting Chinese industries have borne the brunt of these investments. They have not benefited the local population,” the organization says in its recent report.

In Gwanda town, residents say the Mtshabezi River—once a steady water source—has been nearly drained. Chinese trucks, reportedly from a lithium plant in West Nicholson, collect water more than ten times a day using heavy-duty pumps.

“Mtshabezi never used to dry up like this,” says Maparidze, a local taxi driver. “They even put quarry stones in the river to make their access smoother.”

Gwanda Mayor Councillor Thulani Moyo confirmed the issue.

“I’m aware Chinese trucks are extracting water from the Mtshabezi River, but the area falls under ZINWA’s jurisdiction,” he told The Citizen Bulletin.

Maparidze previously worked at a Chinese-run mine in Mberengwa. He describes the experience as traumatic.

“They treat locals like trash. If there’s a misunderstanding, they beat you. Even if it’s reported, nothing happens. They monitor workers harshly, insult you, and make you feel useless.”

He recalls being promised $350 per month, only to receive $150.

“The owner told us we misunderstood that he meant three $50 payments. When we protested, he said we were stupid.”

Maparidze, an ex-miner

Locals also accuse Chinese companies of operating with fake documentation and avoiding registration. CNRG alleges that some companies are unlicensed, but authorities appear unwilling to act.

“These investments are killing our small businesses. We can’t compete,” says a local entrepreneur who spoke off the record.

CNRG also reports that most dams in the area are at critical levels, with water mainly used by mining operations. Fishing with electric shockers continues unchecked, even during peak heat periods.

Siziba adds, “From August until the rains come, they keep killing fish. It’s against the rules, but no one stops them.”

Efforts to reach directors of the Chinese firms — who are generally inaccessible and rarely speak publicly — were unsuccessful.

Findings from the Information for Development Trust’s 2023 report, “Purses and Curses: Impact of Chinese Mining in Zimbabwe,” echo the frustrations of Gwanda residents.

While Chinese investments are often framed as economic lifelines, the report documents a pattern of environmental damage, social disruption, and broken promises—worsened by poor transparency, sudden closures, and weak regulatory oversight.

Editor’s note: Names marked with an asterisk (*) have been changed to protect sources.