Water can seem endless: it covers 70% of the earth’s surface, yet climate change is making the world’s water supply unreliable.

Bulawayo is currently facing one of its worst water challenges in years exacerbated by the El-Niño induced drought.

With ever changing weather patterns due to climate change, recurring droughts have led to severe water challenges amid increasing demand and decreasing supply.

In 2024, the Bulawayo City Council (BCC) started implementing a tight water rationing regime in a desperate attempt to salvage the little left at the city’s supply dams.

Amidst the crisis, calls for privatization as an urgent intervention to meet rising demand have started to grow louder.

“Privatization of water for Bulawayo is something that needs to be considered thoroughly and can’t run along by itself but can work hand in hand with the (central) government,” argues Thabani Singwango, a climate advocate and Geographic Information System (GIS) specialist.

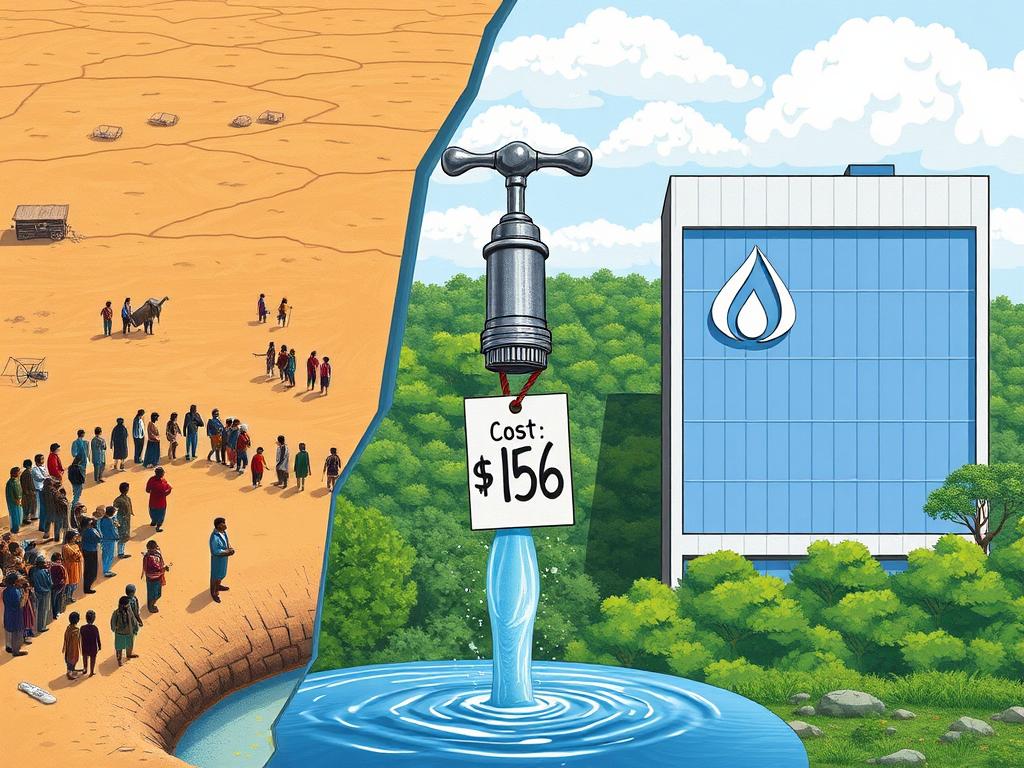

He, however, calls this “a complex issue that often exacerbates inequality in accessing water through pricing,” where companies prioritize profit.

Bulawayo: Water as a right or a commodity? | Illustration generated using Poe, OpenAI

Water privatization typically involves a private company taking over the management and operation of a water system, often through a lease or concession agreement with the council.

This can include responsibilities like infrastructure maintenance, billing, and customer service.

The private company may also invest in upgrades and expansions.

Research shows that local authorities are turning to water privatisation as they struggle to meet demand primarily due to climate change.

United Nations estimates show that during the last century alone, water use exceeded the rate of population growth.

The agency estimates more than one in six people worldwide do not have access to enough safe water a day to meet basic needs.

With the economic hardships forcing more people to migrate to cities, existing infrastructure as that of Bulawayo is creaking.

In Bulawayo, the water crisis is further exacerbated by aging water infrastructure, which has resulted in more than 48% of water sources classified as non-revenue.

Bulawayo’s water infrastructure is a vital yet often neglected lifeline for the City. | Photo: Freepik

Proposed solutions to the water crisis have failed to meet the needs of the city’s growing population of over 600 000 residents, according to the 2022 census carried out by the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZimStats).

A report by the Transnational Institute (TNI), Public Services International Research Unit and the Multinational Observatory suggests that 180 cities and communities in 35 countries, including Buenos Aires, Johannesburg, Paris, Accra, Berlin, La Paz, Maputo and Kuala Lumpur, have all “re-municipalised” their water systems in the past decade.

A proposal for water privatization by the BCC was met with strong opposition from residents.

The municipality had planned to establish a private water and sanitation utility in partnership with a Dutch company, Vitens Evides International.

The Bulawayo Progressive Residents Association (BPRA), however, expressed concerns that this move could lead to higher costs for water and infringe on the constitutional rights of residents to access the precious liquid.

BPRA also criticized the lack of transparency in the process, particularly regarding the selection criteria for the Dutch company.

They also questioned the financial implications of setting up the utility and whether the costs will be passed on to residents.

The advocacy group reiterated its willingness to take action to prevent the initiative from proceeding, arguing that it was initiated without adequate consultation with residents.

Hardlife Mudzingwa, a water activist, warns that water privatization will exacerbate the challenges faced by residents rather than solve them.

“I don’t think privatization of water is the solution. What we are facing is limited access to water for citizens,” says Mudzingwa, the National Coordinator of the Community Water Alliance. “Any solution should address the root causes of the problem. The assumption of those pushing for privatization is that local authorities are failing, so we need to give water services to private entities,” he adds.

Mudzingwa emphasizes governance as the core issue rather than resources, pointing to the financial strain caused by composite billing systems. These systems bundle charges for services such as refuse collection—often not delivered—with water bills, creating unnecessary financial burdens for residents.

Residents lament the burden of composite billing systems, which force them to pay for often undelivered services. | Photo: Freepik

“Privatization comes with exorbitant charges and issues around affordability, which will only worsen the challenges we are facing,” Mudzingwa says. He also warns that such measures could lead to social risks, including disease outbreaks and potential civil conflicts.

Academic research underscores Mudzingwa’s concerns. In the journal article “An Assessment of Law and Practice of the Right to Water: Evidence from Zimbabwe,” Jephias Mapuva links Zimbabwe’s water privatization efforts to the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP) of the 1990s. He explains that the commercialization of public entities, including water services, was a key feature of ESAP, but notes that these initiatives have often been misapplied, leaving marginalized communities with limited access to water.

Similarly, a study titled “Commercialisation of Water Supply in Zimbabwe and Its Effects on the Poor: A Working Framework” by Tinashe Mukonavanhu and colleagues examines the impact of neoliberal policies on water provision. The researchers found that the commercialization of water services has heightened poverty levels as many residents cannot afford the increased costs associated with privatized water supply. The study advocates for a balanced approach that ensures equitable access to water while addressing economic sustainability.

Adding to the urgency of the crisis, a recent report by the Zimbabwe Multi-Donor Trust Fund (Zimfund) reveals that Bulawayo requires US$55 million in the short term to repair its water and sanitation infrastructure.

In response to reports suggesting plans to privatize water services, Bulawayo mayor David Coltart clarified the city’s intentions.

“There is no intention to make the department a private business, but a stand-alone asset for the council that would ring-fence revenue for water and sanitation projects,” Coltart said during a press briefing in 2024.

Coltart explained that historically, revenue generated from water services had been diverted to other council activities. “With this project, all surplus revenue will be used for specific programmes related to water and sanitation,” he said, emphasizing that the move is aimed at better management rather than privatization.

In a recent meeting, Town Clerk Christopher Dube emphasized the need for a municipally owned water utility as a countermeasure to the ongoing push for privatization by the government. He warned that failure to proceed with this proposal could lead to the government imposing privatization, which would leave the city without control over its water supply.

While no national policy explicitly promotes full-scale water privatization, government agencies have acknowledged the need for innovative financing models to tackle the growing urban water crisis. The debate continues over whether private sector participation should be expanded, with advocates pointing to successful PPPs in other sectors and critics warning of the risks of inequality and increased costs for consumers.